I have been thinking about my mom lately.

I find myself thinking of random memories of her. That time she pretended to cut my hair and just snipped some bangs, waved her arms around my head while snapping the scissors, and then asked me to look in the mirror – I told her it looked great. My best friend, with his view of the whole thing, laughed his head off. The two of us driving at night even though she had a hard time seeing and I had to “be her eyes” so we didn’t hit anything. Music she introduced me to – she’s the reason I love Bon Jovi and anything 80s. Books she and I read and talked about. She is probably a huge reason why I am a teacher today. I’ve been thinking of all kinds of memories. Even little things I said I’d do, like bring home one of those darn Chinese Zodiac stuffed dragons.

She asked about that dragon a few times…

And now the Year of the Dragon is fast approaching. Again.

It is the second time this one is coming around for me while living in China. For each new Chinese New Year, they release these little red stuffed animals that correspond to the Chinese Zodiac. Every year, the style is slightly different. The dragon that first year had the exaggerated cartoon features you would expect, but somehow, it still looked very cool. The ones this year just aren’t as good looking. I have this mental image of it hanging from its suction cup on the kitchen window of that first apartment I lived in, but then nothing else. I must have taken it down when I moved. I have no memory of it beyond that. My mother saw it in a video call and said she really wanted one. By then, the season had passed, and I could not find the dragons anywhere. If I had known about TaoBao (China’s Amazon and Ebay combined) then, I could have found it, no problem. I kept promising her that I would get her an entire set soon. Always soon. I’ll look them up. Next time I visit. You’ll have your dragon.

~~~

It has been almost a year now—eleven months—since my mom passed away due to complications with AML and infections. I still talk to her on WeChat. Send her pictures. I told her about Asher learning to ride his bike. Our summer fun. After he broke his arm, I sent her updates. I catch myself wanting to tell her something interesting or ask her questions. I think, “Mom will know. I’ll just send her a…”

I never did get her that dragon. Jade Buddha necklaces, purses, scarves but never the dragon.

I woke up thinking about that this morning. It has been on my mind for a while, actually—this dragon, hanging from my kitchen window, a cute red thing with wings and big eyes that my mom wanted me to get her. The memory, the way memories do, slips into more recent ones about my mom and even older ones. Memory may be set in time, but life has a way of twisting and turning and stretching and pushing layers of lived experiences around in your mind the way the Earth’s layers can be moved closer or farther from the surface of the crust.

I tried to get home every two years to see family, especially my mom. I was only supposed to be in China a year, and so it was always a touchy subject she’d bring up at times – When are you coming home? Will I ever see my son again or my grandson? When I got married here and had a child, I brought them home to meet her. My son was three months old, and that trip was during an Ohio winter. Ohio winters are dismal affairs. It was important to be there that first Christmas with my family. That was the only time my mother held her grandson. His age kept us from returning the following year, and then COVID restrictions kept us in China for a few more.

That Christmas trip was six years ago.

~~~

My mom was diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) last year, in November, and due to complications with infections, her battle was short. When she took a turn for the worst, I came home. Due to the exorbitant airline ticket costs right after China opened up and loosened travel restrictions, only I was able to fly from Dalian back to Ohio.

I felt cracked, fractured. I knew why I returned. I knew what it meant.

Unable to say the words, I turned to what I have turned to many times before: books. I did not want to live in my head, in memory, for the twenty-plus hours of travel.

On the flight over, I finished for what might be the fifth or sixth time, The Sun Also Rises. Hemmingway often gives so much, paradoxically so, if you consider his sparse style, but Jake’s “Isn’t it pretty to think so” left me bereft of hope or solace this time.

I wanted something more from that reading. Something I could not name. I wanted to get off the plane with an epiphany that would steel my nerves or calm my heart. I opened my Raymond Chandler collection next. The small worlds of his stories are usually so vast, like falling into a tiny hole in the ground only to find it is this bottomless well. Something stirred as I read a few, but it was more an amplified version of what I already felt: this yearning, seeking sensation. I think Chandler must have felt it, too, and put it there for others to find. I put him away and pulled out my slim Dickinson collection. It has about 180 of her poems organized by themes such as “Life,” “Love,” and “Eternity.” I’ve written on the back cover a few of the poems that I love but that this editor leaves out. This selection usually has what I’m looking for. I must have read every single poem right then and there. If you cannot find a Dickinson poem that matches your state of mind or the occasion, you’re not looking hard enough. But there on that plane, her lines didn’t fill that need I had.

Due to the infections my mom contracted, her lucidity and coherence was almost nonexistent for about two weeks before I arrived. The doctors prepped me before going into her room. She might not respond to me or recognize me, they said. When I walked in, I didn’t recognize her. She’d lost so much weight and couldn’t hold herself up. All hard angles and sharp points where she used to be smooth, soft.

She stared at the white wall of her hospital room, mumbling something in a whisper while an aide sat in the corner. She’d been trying to take her IVs out and had fallen out of bed a few days before and always needed an aide in her room.

How could this be my mom? She’d video called us that Christmas morning to watch Asher open his gifts. She was at her home, having just gotten back from a hospital stay. She laughed, joked, made squeaky elf voices. We had talked about her plans for New Years…

Right after Christmas, though, she’d gone quiet. For nearly a week I didn’t hear from her. Then on New Year’s Eve she got back. She’d been sent back to the hospital. Infections causing her pain, muscle spasms – Chondritis, she said. As bad as this was on top of everything else, she sounded just like herself. Still able to laugh, complain about Ohio’s weather, talked about her doctors. And then, in a voice message only eleven seconds long, she joked about being so young, that the Leukemia would go away, but that something else would creep up and give her trouble down the road. We talked back and forth until late in the evening, even as 2023 arrived for me and the last day of 2022 ended for her.

And then I didn’t hear from her until January 17th. Three messages, all unintelligible.

M my mmmm MB by one read. Another: X. The third and final message I ever received from her WeChat account: Mp

In the time between our New Year’s Eve conversation and then, my mom’s condition had gone from bad to worse. My brother and family members tried to keep me in the loop, but information was not clear. Things didn’t add up. I couldn’t tell if she was just in a bad stretch – one she could come back from – or if it was something else. No one knew. Or they wouldn’t say. It was early February when my step-dad finally got information that made sense. It is the phone call that brought me home.

And so I was home.

Just then, she looked my way and her eyes lit up. She lifted her arms, and as clear as day, said “Come here and give me a hug.” The aide asked if my mom knew me, and she said, “Well, yeah, that’s my oldest son, Jordan.”

I hugged my mom and cried. I didn’t want to. I couldn’t help it. She…I was not ready. I guess I hugged her until she, like she used to when I was my own son’s age now, told me, “Don’t cry, my boy. Don’t cry.”

I was with her for the last three weeks of her life. During this time, she was more lucid and coherent than she’d been in weeks. Her team of doctors couldn’t believe it. She was talking, joking, laughing. I spent as much time with her as I could. I had room and board at the Cleveland Clinic’s Hope Lodge but ended up just staying the night in her room with her, sleeping in the recliner there. In some ways, I felt like a kid again. She and I talked and talked. On February 16, she and I were just chatting, when she took my hand and said, “That’s what I yearn for. I yearn for that time with you boys. Some people complain about their kids – oh, they’re being annoying – and so on, but not me. I love being a mom. It’s been the greatest blessing to just have been your mom and raise you.”

We talked about memories, dreams, and about her cancer. She knew she was dying, but never got angry and never cried about it. I am still in awe of her courage and the peace she seemed to have found. We caught a Rocky marathon on AMC one day, laughed about bad day-time TV, looked at family photos, discussed good books, and ate our favorite Mexican dishes from the restaurant we used to go to when I was younger.

When she slept, snuggled in her blankets, her beanie on her head, huddled in a ball, she looked like a baby. It was hard to reconcile what I saw with what the doctors told us. Sometimes she talked and ate almost like normal. She can’t be dying! Other times, she retreated into herself and her bed. And I knew.

Sometimes she saw things, but mostly knew they weren’t real. She saw her old dog, Dallas, a lot. She loved that poodle so much it’s ridiculous. There were times when she thought she’d been smoking. Would ask me to find the cigarette she dropped in the bed. Once she asked me to make sure all the animals were out of the room because they kept biting her toes. Out of nowhere, she once said, “I’d rather you not use that word, ‘ministry,’ because, you know, the Pope’s dead.” I looked and her and said, “Mom, we’re not Catholic.” A lot of the time, she knew when she was getting loopy. She’d say so herself. I got into the habit of asking the same four questions at the beginning of each day, something I picked up from the nurses: Who am I? What’s your full name? Where are we? When’s your birthday? On good days, she’d tell me to knock it off.

When it became necessary to move from the hospital to a hospice home, I stayed with her there, too. Even in that decision, she showed me what it means to face your life and death with grace.

Her doctors had suspended active treatment for her Leukemia and the serious abdominal infections because of her body’s adverse reactions. Her swollen torso and constant pain made it impossible for them to continue anything more than pain management. They needed her room if she was not going to be receiving treatment, they said tactfully but clearly. The Friday before, five days after I arrived, her team sat the family down for a meeting. They laid out the choices: resume mom’s treatment and cause her more immediate pain and do, in their view, little overall good, or begin transitioning her to hospice care. We had the weekend to think.

My grandparents, my brother, my aunt, my step-dad, we were the family. But in the end, it was me who made the choice. I chose to talk to my mom about it. That Sunday, February 19, when she was crystal clear, surrounded by family and her close friend she’d not seen in years, I talked to her about her choices.

Her friend had just painted her nails. She began talking about her feelings, about waking up some days not knowing where she was and other times knowing. Her voice was low but strong. Always this raspy, airy quality to it. She wasn’t angry, but she knew she didn’t want to feel this way. It was as though she knew she had a choice to make, even though she hadn’t been in that meeting. She started the conversation when it was too hard for us to.

“Mom,” I said when I realized where her mind and heart were heading, “knowing what you just said, what do you want?”

“I want to go home. I know it’s not going to be much longer. I want to go home. I don’t want to spend my days in here.”

I reminded her that she needed rest and a clean, peaceful place and people watching her. Because of where she had been living before getting sick, that place was no longer an option, and she knew that. But she wanted to go. Get out of the hospital.

“I have another question, okay,” I said. “And I want you to really think about it.”

The words…words I needed to say, would not leave my mouth. In a room full of people, I dropped my head and let the tears fall. It was so important that she help us make this choice, that she understood. And I couldn’t do my part.

“Don’t cry, my boy. It’s okay. Come here.”

I took her hand in mine, or she took mine in hers. The next words I spoke, words I still sometimes hear in my head, came slowly and painfully; her responses, her slow and deliberate answers, I still hear them almost every day.

“Mom we have two choices, okay. I need you to understand this. Both of them, both mean you’re fighting. Both mean you’re fighting. Here’s choice one. Choice one is that on Monday they try to put medicine in you. They put the stuff you had in a while ago. That means tests and pokes and the other stuff. That’s choice one. That’s Monday. That’s choice one. On Tuesday we’ll know if it’s working. Option two. Option two is Monday we tell them that we don’t like the hospital. We don’t like the shit in your nose. We get out of here. Go to a place where you can be comfortable and be closer to people who love you. That’s where you’ll be when you…Mom. Do you know what you want to do?”

She nodded. Slow. She looked at her hands and then at my brother and back at me.

“It is so hard to choose. The second choice will let me take the end on my terms. Peacefulness. Without all that crap in my face. You know I hate drugs and all that. And the first one, you know, it’s let’s try this and then that. I’m sick of that. Am I jumping the gun here? You know, I don’t think so. I think this will go on and on. And I don’t want to drag you kids through that.”

“Mom, it’s not about us.”

“Well, it is to me. It is to me. It’s always been about that. And I always said that when it was my time, I would not want to drag it out. You know, we talked about that a lot. And I think that if that’s the way I’m supposed to go, then that’s the way I’m supposed to go. Die in my sleep. But at least I’ll be around the people I love.”

She looked around the room then again. At each of us.

“But I never thought it would happen this soon. I’m so young.” She squeezed my hands and smiled. “But you know what? You and your brother bring out the best in me. And Asher will get to,” she laughed at the thought of him, “he’ll get to hold on to it. It’s okay.”

Two days later we moved her into the hospice home.

~~~

As the oldest son, despite all the family around, it fell to me to make many of the final choices. During this painful ordeal, the last things you want to deal with are financial, legal, and logistic details. But you have to. I did the best I could—arranged everything possible, signed papers, made the phone calls. My stepdad, his girlfriend, and my aunt, my mom’s youngest sister, were lifesavers. They helped so much. It would not have been possible – nothing would have been possible – without them. Beyond just being a ride taking me places, my step-dad and his girlfriend were these rocks that just supported me the whole time, kept me moving and my head clear. At some point, my aunt set up a GoFundMe page, and friends and family around the world donated to help cover crazy costs that kept coming up. It was remarkable and incredibly touching.

My aunt is a wonderful singer. She used to sing at family events, and I remember thinking how amazing her voice was. When she had time alone with mom, she sang to her songs they both loved. On one afternoon, close to the end, she and her daughters brought bubbles for my mom. The four of them sat in her room, laughing, and telling stories—and blowing bubbles like kids. My mom had the heart of a child – open and loving and willing to just believe in people. It sometimes got her in trouble or got her feelings hurt, but she refused to change. Live well. Laugh often. Love much. As trivial as it may sound, this kitchen motto was indeed one she embodied without irony or regret.

I knew I had to return to China. My wife and son were struggling, work was making demands, and the longer I put off buying a return flight, the more expensive it became. It was an impossible decision. I knew that if I left, I would not be there when she passed. No matter what the date was when I bought the ticket, I just knew in my heart that I was not going to be there by her side when she left this world. The thought paralyzed me. I didn’t know what to do. I did the only thing that made sense. I asked my mom for advice.

She told me to get my butt back home to her daughter-in-law and grandson because they needed me. And when I cried, she hugged me and once again said, “Don’t cry, my boy. Don’t cry.”

I thought coming home was hard. Leaving nearly broke me.

Meetings with hospice nurses were painful. Every night was hard. I stayed with her constantly. When she tossed and turned, the pain flared up, she needed to talk or just be listened to, I was there. People from her life – many I hadn’t seen in years – came by. There was a lot of love.

Her lucidity went in and out more frequently that last week. Even so, she knew me the whole time. There is no doubt. She always knew my name, and that I was her son. Even when she didn’t know where she was, she remembered that.

The last words I spoke to my mother were simple and true.

“I love you so much. I’ll see you again, mom. I’ll see you again.”

~~~

On the flight back to China, I began reading Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan. His worldview is one that slaps you around a bit but for a good purpose. I’d never read this one before and hoped for the best. My mind and thoughts were absolutely fried. Exhausted, stressed – these words don’t even cut it. I had to distract myself. A few dozen pages into the book, I put it down. His voice, the absurd qualities of Malachi Constant’s tale, the plot – something about it wasn’t working for me just then.

For weeks after returning to China and my mom’s passing, I kept searching for a way to make my mom’s death make sense or my feelings…just calmer and clearer. An episode on a literature podcast I like ran a show about a book called Three Roads Back. A book about how well-known writers dealt with grief in their life. I scoured the web for what I could find of the three writers and how they overcame the loss in their lives. Again, the stories and lessons were powerful, but not what I needed. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is a favorite of mine, too. I found her Notes on Grief that she wrote after the passing of her father. Her work is so intimate and personal that I read it and was put into her grief.

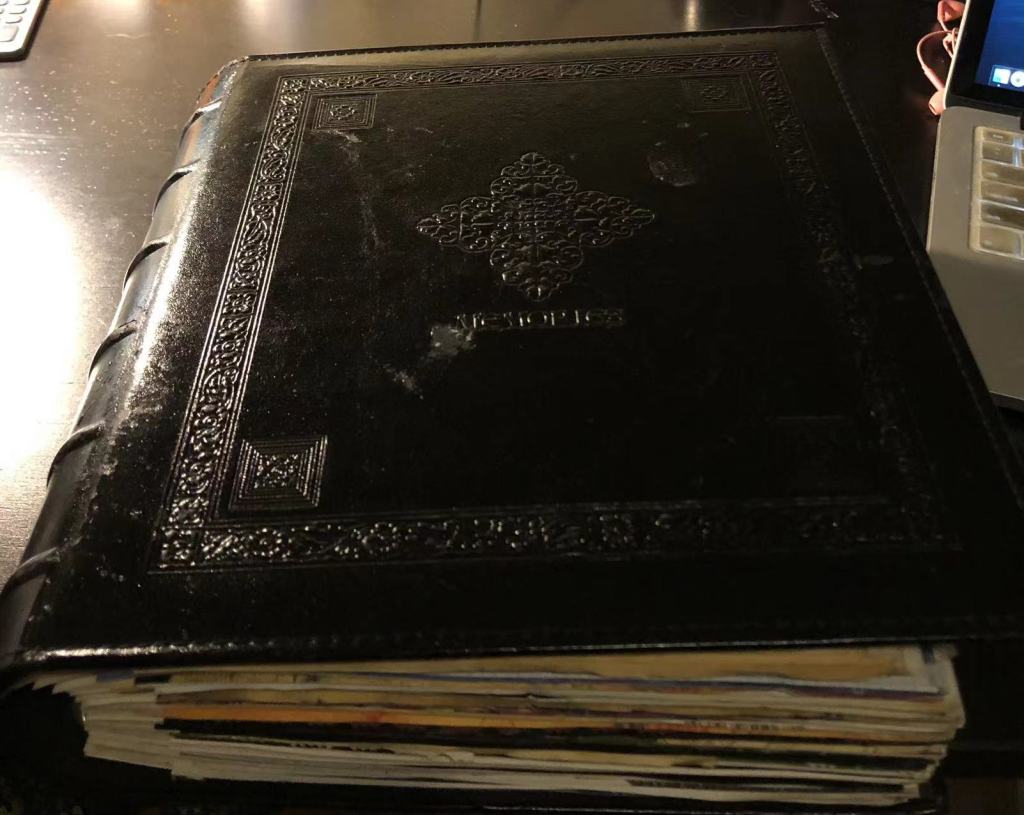

And then I found my old high school senior scrap book. It was one of the things I brought back from Ohio. Just looking at it brought back the memories of when I sat at our dining table with my mother and put it together.

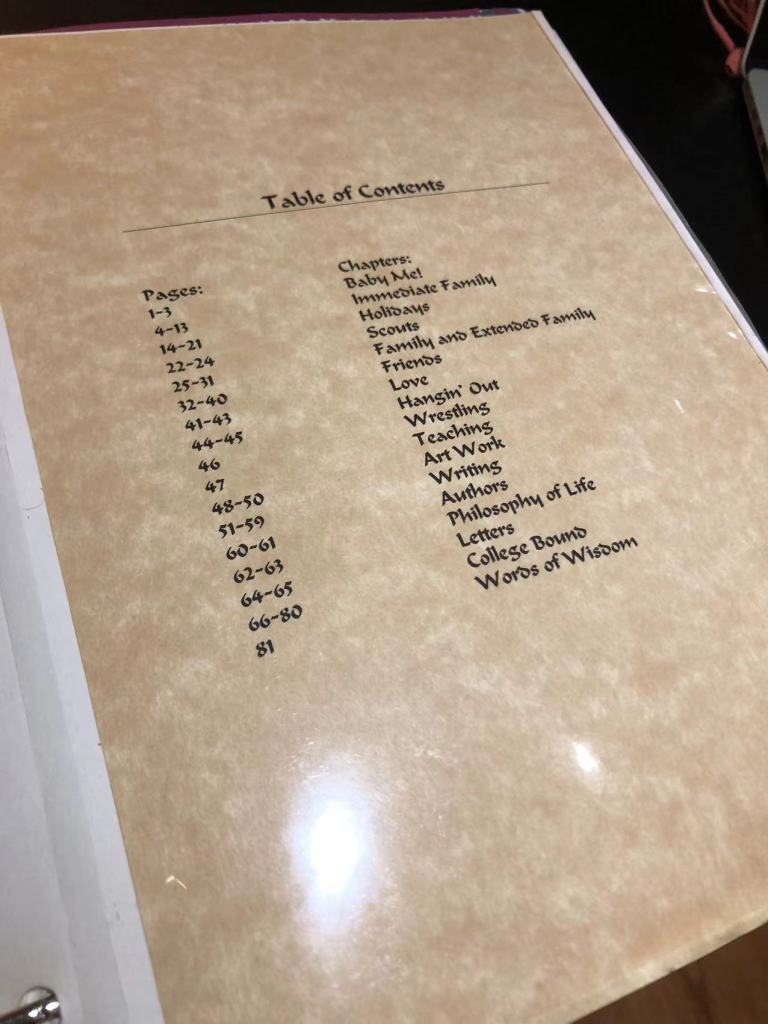

This scrap book is something else. My senior English teacher had all of us put together scrap books of our lives as a big project. I started on mine much too late to make anything special on my own. But when I complained that I was probably not going to do well and told my mom about it, she lit up and said she’d help.

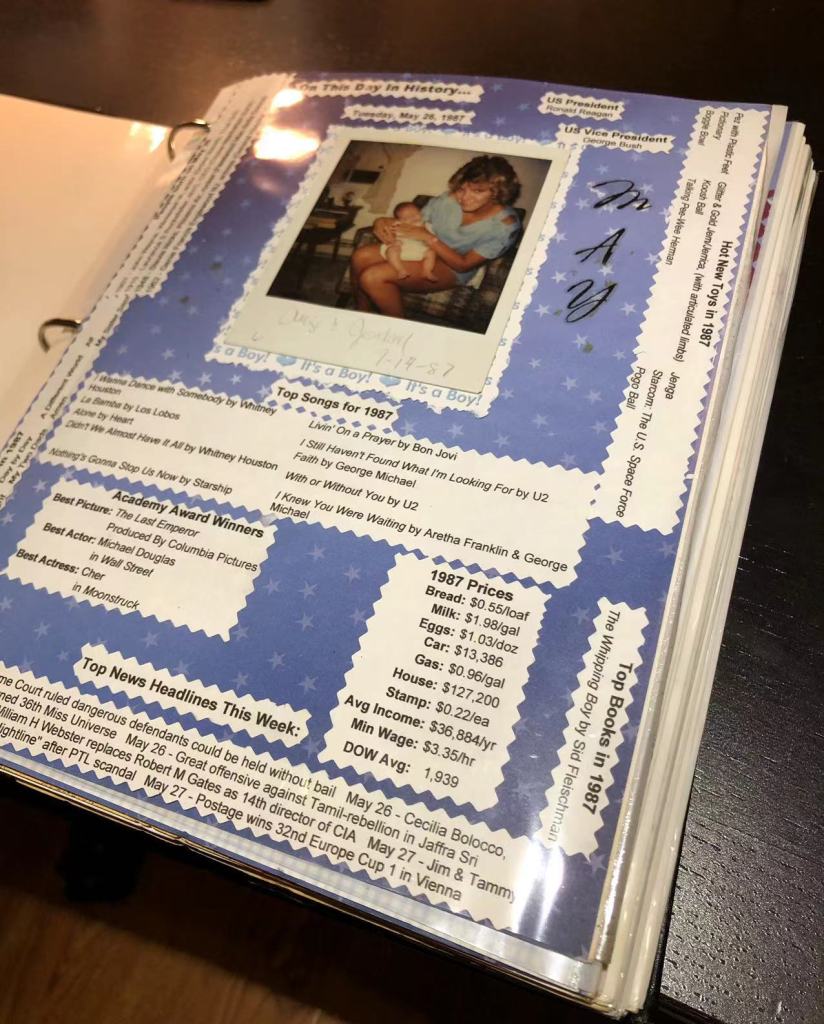

Over a two-week period, she and I poured over hundreds of family pictures, wrote up captions, cut out crafty inserts, and brought to life what I now consider a family heirloom. We designed the scrap book to look like an actual novel. We bought a thick binder that looked like an old-fashioned leather book and organized all the pages and sections as chapters. I remember those two weeks that we worked on it. I wanted to go out with my girlfriend and friends. As a sixteen-year-old, I wanted to do just about anything else but work on an arts and crafts project with my mom. But I stuck it out, and we worked side-by-side on this book that is now on the shelf behind me in my office here in China. This is a huge book. It includes pages with my pregnant mother, my first photos, family pictures from trips, holidays, and normal goofiness. Friends and pets and all kinds of stuff are in it. The teacher had us write a series of letters to important people in our lives – friends, siblings, parents. The letter I wrote to my mom is in there.

When I found it again after getting back from the States, I reread it. The letter and the whole scrap book. And then…

Something happened. Looking at my family, seeing our faces, reading the words I had written when I was younger…and then thinking about my own wife and son now…I saw the story I was already writing with them. The one my mom helped write in her time, the one she shared with me and helped me start. It occurred to me then that the reason I couldn’t find what I thought I needed in books, in literature, was because a part of a story’s power comes from the reader somehow recognizing a piece himself on the page.

No story encompasses all of what you may feel, and it doesn’t teach you how to deal with your specific troubles or take them away. We find pieces of ourselves in the books that we read because the stories they tell, they’re not always maps or instructions, they’re dreams and nightmares, wishes and hopes. They are messages in bottles. They’re shooting stars that we see and watch with wonder and sometimes fear and awe or curiosity. They are voices that remind us, over and over again, that even though we must do the walking, go through the heartbreak, the excitement, the pain, the loss that life brings, even though we have to go through it ourselves, find our own way, we are not alone.

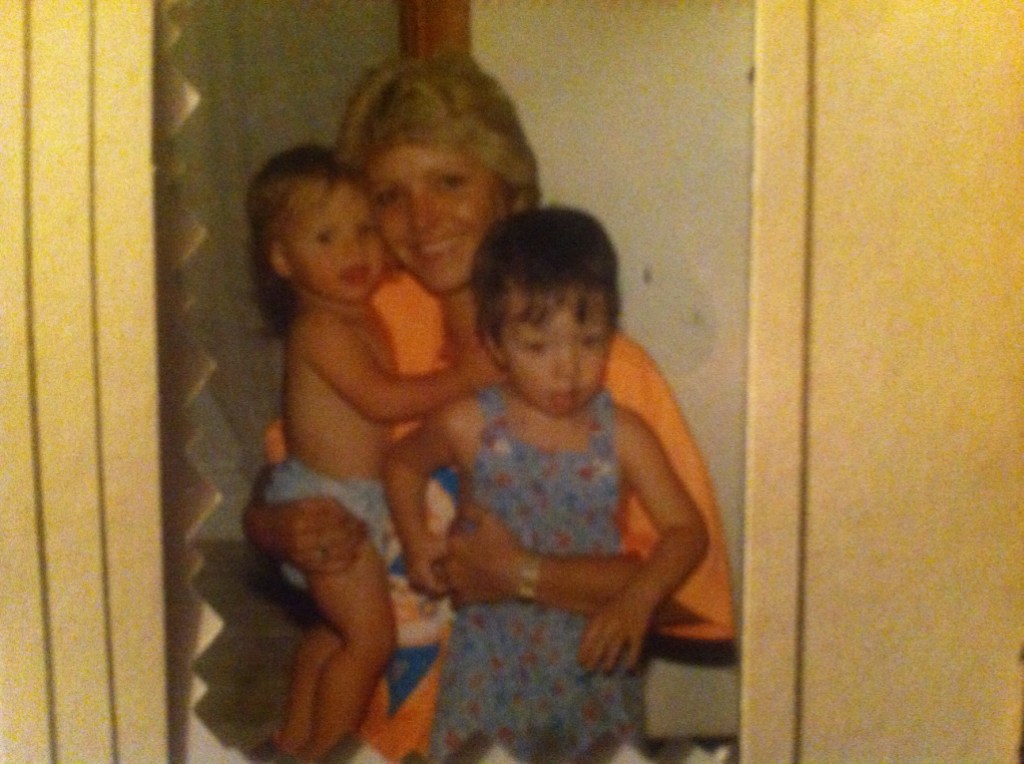

I am still working through the death of my mother. She was only 55. I thought I had more time with her. I wanted my son to know her. I wanted her to laugh with him and tell him stories about how troublesome his father was when he was a kid. I wanted him to see how cool she was, see all her crazy hair styles and colors, see how brave and loving she was. It is up to me now, to tell her story to him. To bring her to life for him. It is a task I’m up to, even if it still hurts.

My mom used to read a book a day when I was a kid. We’d get to the line at the bank or the pharmacy, and while my brother and I ran through the aisles, she’d stand there and read. It wasn’t long before I became interested in what she read. I’d ask about the story, and she’d explain what she could. When I was an angsty teen writing short stories and poetry, she encouraged me. She helped me select poems to submit to competitions, and let me bounce ideas off her, even really bad ones that involved vampires (I was fourteen!). She brought the world of literature to me, opened it up and made it a part of my life. I now have a book in hand or in my backpack wherever I go. My son sees this and asks about the stories I’m reading, just like I did.

All the books I read, searching for a way to process my mom’s sickness and then her death, those could never have done what I asked them to do because I wanted a book to deal with the pain, take it away. Books don’t do that. They walk with you through the pain.

My mom passed away at 9:25 pm, March 4th Ohio time. 10:25 am, March 5th China time.

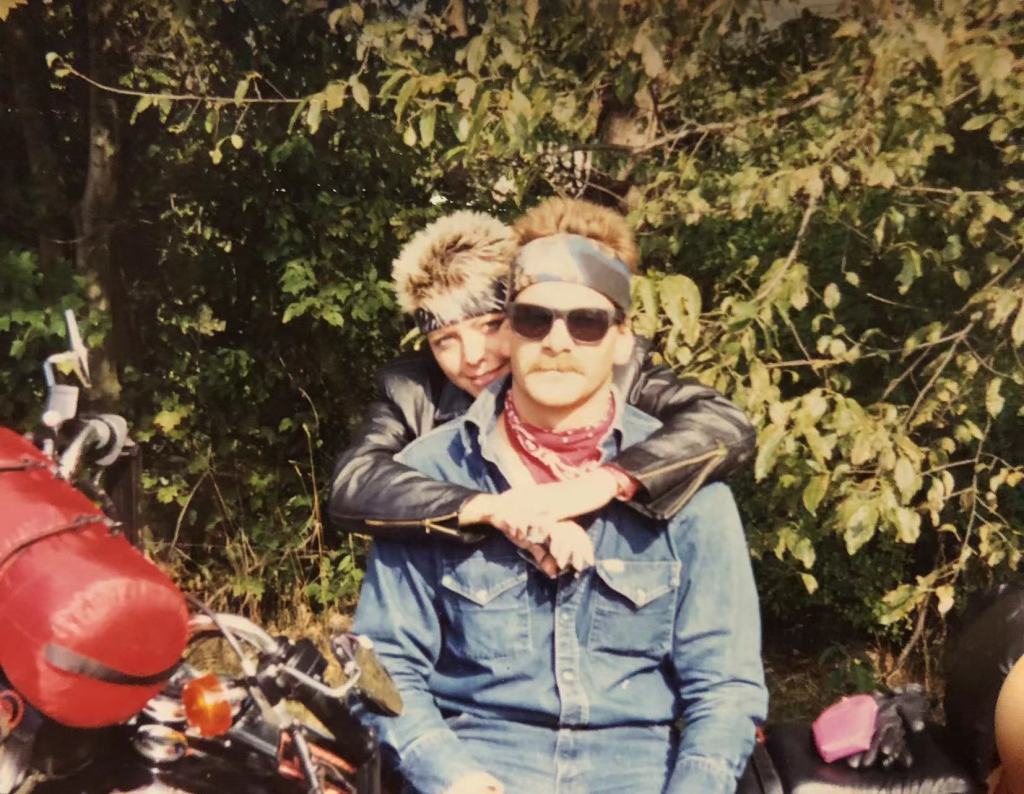

I think about those three weeks I spent at her side a lot. That time is mixed in with all my memories of her now. I see her in her hospital bed, her eyes shining brighter than what you think is possible. My aunt putting lotion on her arms to keep her skin and all the tattoos smooth. I see her hugging my wife and holding my son as a baby. I see her laughing at something ridiculous my brother has said just before the camera takes the picture, the one I have hanging up in my classroom with a bunch of other family photos. She’s telling a sixteen-year-old me that I can get a tattoo if I want. I see her on my step-dad’s Harley, decked out in leather. Her hair is short, blonde, and spikey. I see her in her white wedding dress, styled after a western cowboy theme, standing next to my brother and me as we give her away. I mess up and try to say my line twice before finally getting it right. We’re all traveling to NYC together, hanging out and eating cheap food to save money. I see her dancing in the kitchen to Motown with my brother. I see her fighting through depression, teaching me how to do it, too. I see her excited, standing in line with her sister and me and my wife at Cedar Point, waiting for our turn to ride. I see her smiling and crying as I come out of customs at the airport, arms up, waiting for a hug. I see all these memories and more.

I have been thinking about my mom a lot lately, but I have also been telling my son about her, too. He will know his grandma. That’s a promise I can keep.